A long journey, a long table

“El ke alarga la meza, Alarga la vida.” This is a Sephardic Ladino expression, emphasizing the importance of long convivial tables. It can be translated as the ones who have a long-crowded table, elongates their life, or one who expands the table, expands life, or simply the more the merrier! The story of Sephardic Jews became a demonstration of this expression. Their culinary culture continues to survive here in Türkiye, a legacy reaching from across the other side of the Mediterranean, from the Iberian Peninsula to Anatolia.

More than half a millennia ago, a long voyage was about to start at the shores of today’s Spain.

In 1492, the Jews of Spain, the Sephardim were expelled from their motherland, and for many, their new home became the Ottoman Empire. For more than 500 years, Sephardic food and eating habits were largely reserved in Ottoman lands, probably because the Spanish-Jewish food culture and its contemporary Ottoman counterpart already had an affinity with one another.

Both culinary cultures were greatly affected by medieval Arab cookery, having lots of tastes and flavors in common. Moreover, they belonged to a similar geography, on the same climatic band, with similar practices of agriculture. Though it was a tough journey for the expelled Jews, their new home was not totally an alien land, at least culinary-wise. Both food cultures had a shared heritage, and tastes were already familiar. Eggplants were one example, a marker of Jewish identity in Spain, this vegetable almost unknown to Christian culture in Europe, was also a dominant ingredient in Ottoman cooking.

There were also other ingredients to which the newly arrived immigrants had easy access and whose names would not sound at all different to the Jewish immigrants, such as olives and spinach. Interestingly enough, olives, zeytin in Turkish and aceituna in Ladino, and spinach, ıspanak in Turkish and espinaka in Ladino, were derived from Arabic and Persian languages. Besides the ingredients, certain tastes, too, must have been strikingly familiar.

Tastes for both sour and sweet traveled together with the Sephardic Jews, only to meet a culture that already had a taste for the same. Istanbul was home to sour dishes and the Ottomans’ liking for sour flavors is well recorded. To begin with, the 15th-century Ottoman cookbook written by Muhammed bin Mahmud Şirvani listed sour dishes as its first chapter. Additionally, right before the Jewish immigrants arrived, Mehmed the Conqueror used to have a soup made of sour plums. The Ottoman palace registries from the 15th and 16th centuries include fresh sour or unripe grapes, as well as sour and unripe plums, and specifically sour pomegranates, lemon, and bitter (sour) oranges.

Similar to the sour plum sauce that Mehmed the Conqueror used to enjoy with chicken, one of the most characteristic dishes in today’s Turkish Sephardic kitchen is called gaya kon avramila, fish in sour plum sauce. Traditionally rooted hallmark tastes like agristada, avramila and ajada all emphasize sourness. Even up to today, modern-day sour Sephardic dishes include “kaşkarikas kon avramila” (zucchini peel with sour plum sauce), “agristada de meoyo” (brain in sour sauce), “agristada de yullikas” (meatballs in sour sauce) and “avramila kon uevos” (eggs in sour plum sauce), “pişkado kon uevo i limon” (fish with parsley and lemon) and “agristada de pişkado” (fish with sour sauce), all demonstrating a distinct fondness to sourness. Such examples are countless, and now we have a new opportunity to see many more tastes that bond Spain and Türkiye through the Sephardic long voyage in a new exhibition in Istanbul. The exhibition “Sephardic Flavors and Aromas” opened at The Quincentennial Foundation, Museum of Turkish Jews, brings us to this long table with the collaboration of Red de Juderías de España, the Embassy of Spain and the Istanbul Cervantes Institute.

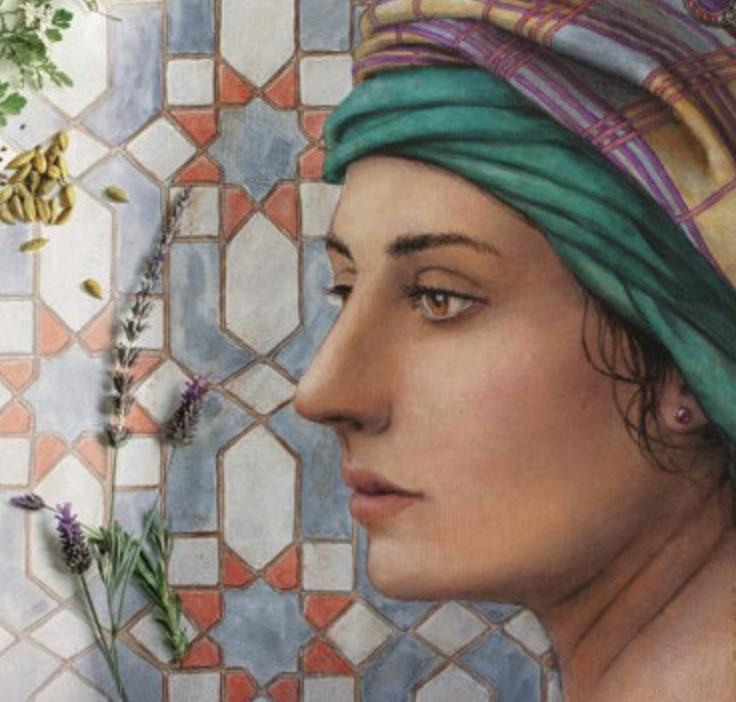

Red de Juderías de España, dedicated to research, preserve, disseminate and promote Sephardic culture, has created this exhibition to bring attention to Sephardic cuisine and history. Based on the book Sabores de Sefarad, written for Red de Juderías by writer, chef and food photographer Javier Zafra, the exhibition features 27 works by the artist. Accompanied by historical notes, gastronomic discoveries and inspiring images, participants will be taken on a journey through time, where the palate as well as the heart will guide them deeper into this heritage.

Just as Istanbul is a city that embraces Sephardic flavors, the 500th Year, Museum of Turkish Jews next to the Galata Tower is the ideal place to host such an exhibition. Just steps away from the museum, one can trace back to history, a careful eye will notice names of Sephardic Jewish families engraved in stone above entrance gates, as the neighborhood was the hub of well-off Jewish community. The Jewish old people’s house Barınyurt is close by, the very first Turkish-English cookbook on Sephardic cooking in Istanbul was compiled from the recipes given by the elderly living there. It has been a very very long table for them, some could still talk about the dishes that were slowly fading away, some in danger of being forgotten forever.

Chef Javier Zafra’s work is remarkable to document Sephardic flavors reaching today from the past. However, his expedition journey was not over, his trips in Istanbul and beyond continued, at each step finding something common in Turkish and Sephardic cuisines. He kept posting his findings on his Instagram account. He was amazed by the rolled candied bitter orange peels in Çiya at Kadıköy, they were almost identical with the Sephardic candied citrus peel, except that they were not threaded in a rope. He could not help but try to find a link between the famed “Testi Kebabı” which has become a tourist fare in Cappadocia to the Jewish “adafina,” a classic Sephardic Sabbath stew, cooked all night long, buried in embers.

His quest for finding new connections must be an inspiration for all of us who are curious about finding similarities between cultures, and food is sometimes a common language we all speak. As the Ladino expression says, if we enlarge our culinary expedition and find more about our cultures, our table will be longer to share, conviviality will expand, and we all know that the more, the merrier!